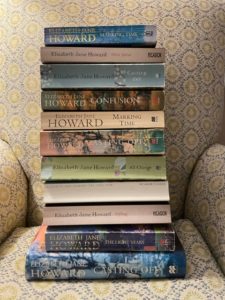

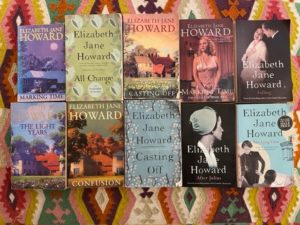

Elizabeth Jane Howard is just one of the greatly underappreciated female writers of the modern age. She was born in 1923 to wealthy but unhappy and dysfunctional parents, which means that a streak of dark melancholy is to be found through all of her writing. It never fails to take the reader by surprise. The first four books of the Cazalet Chronicles were written in the early nineties and describe an upper-middle class family living through the war in the Sussex countryside. When the first novel in the trilogy, The Light Years, opens in 1937, you expect a cosy, family saga written by a woman, for women. This is not what you get. The trilogy exposes the vulnerability of its characters, who although are protected by their wealth up to a point, do not feel the security they so greatly desire. They have money but they don’t really know where it comes from or whether it will continue to appear. They have emotions but they don’t really know how to express them, and the war could mean the loss of everything they hold dear. These books are not cosy at all.

Elizabeth Jane (known as Jane) was not really given an education. She had the odd governess at home and briefly attended Francis Holland School before leaving to attend secretarial college. At the age of nineteen she married thirty-two-year-old naturist, Peter Scott. The marriage was unhappy from the start, as Jane longed to work and to write. This intense part of life was described beautifully in her 2002 memoir, Slipstream. In 1943, Elizabeth Jane Howard gave birth to a daughter, Nicola, but soon afterwards abandoned both the baby and her husband to go and concentrate on her writing, feeling that she couldn’t do both if she was to succeed at either. She went to live in a flat off Baker Street which she has described as “a bare bulb in the ceiling, wooden floors full of malignant nails … the only thing I was sure of was that I wanted to write.”

And write she did.

The Beautiful Visit was written in 1950, when Jane was twenty-seven. It is so assured and distinctive that the novel appears to come from the pen of a much older person. It won the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize in 1951 for best novel by a writer under thirty.

The Long View was published in 1956, and the journalist Angela Lambert has asked why it is not recognised as one of the great novels of the 20th century. It tells the story of Antonia Fleming, who is living in London in the 1950s and facing the prospect of a life alone. Her children are adults and her husband is a stranger. The narrative works backwards from this point, tracing Antonia’s relationship with her husband back to their first meeting in 1920. It is an extraordinary piece of writing, which never seems to leave the memory. Hilary Mantel is a huge fan of the book and noted that

Conrad Fleming seeks to mould Antonia. He is a man of unblemished conceit, immaculate selfishness. Young female readers today may view him with incredulity. They should not. He is faithfully recorded. He is the voice of the day before yesterday, and also the voice of the ages past.

Elizabeth Jane Howard writes so subtly about the women of her time, and how ingrained it was that they should remain subservient to their husbands.

After a brief marriage to Jim Douglas-Henry in 1958, Jane married Kingsley Amis in 1965. She was a loving and interested step-mother to his three children and spent her time cooking and tending to the garden of their house in Barnet. Amis was a great writer and his talent needed to be nurtured. When she had time, Jane did a bit of writing too. She said in the Observer to Elizabeth Day, “I think I certainly had to be second fiddle … I really couldn’t write very much when I was married to him because I had a very large household to keep up and Kingsley wasn’t one to boil an egg, if you know what I mean.”

Her step-son, Martin Amis, cites Jane as a huge influence on his writing. She spotted the talent in the teenaged layabout and got him reading (first Austen and then everything else) and then to Oxford. In his memoirs, Martin placed her – as a novelist – in the august company of Iris Murdoch, praising her “poetic eye” and “penetrating sanity”. “She salvaged my schooling and I owe her an unknowable debt for that”, he later said.

Jane’s marriage to Kingsley Amis became increasingly tempestuous and fraught, until she left him in 1980. His anger was renowned, and he wrote very publicly about his hatred of Howard and how meeting her was the worst thing that had ever happened to him. She never retaliated in print. Unsurprisingly, Jane’s writing life improved drastically after her marriage ended and she started producing great work again.

Elizabeth Jane Howard blames her three failed marriages and her numerous affairs on her difficult relationship with her mother, who she believed never liked her. She has said “I was a tart for affection most of my life”. After a rocky start, her relationship with her daughter, Nicola, improved hugely in later life. She had left her child with her father, presuming she would have a better life with him as he was more financially secure. This was just one of her decisions that she later came to regret.

From 1990, Howard lived in a sprawling house in Suffolk. She tended her garden and had some success with the Cazalet Series, but still she was lonely. After appearing on Desert Island Discs in 1995, she was contacted by a man who she started corresponding with. Soon a relationship had started, and according to her great friend, the writer Selina Hastings, Howard was as giddy as a schoolgirl aged seventy-two. As Nicola got to know this man, she realised something was wrong. A private detective was employed, who reported to the family that he had a history of convicted violence, an ex-wife who died of a brain injury and an obsession with famous women. Jane managed to escape unscathed but was left disappointed and humiliated. But in 1999, she wrote Falling, an account of her experiences at the hands of this stalker. Psychiatrists have claimed it is the best portrait of a psychopath that they have ever read.

Although Howard steered clear of men after this incident, she had a peaceful and productive old age, publishing the last of the Cazalet Trilogy, All Change in 2013, aged ninety. She said at the time, “Sometimes I don’t feel any age at all. I feel quite, sort of, naive and open to things.”

Elizabeth Jane Howard died the following year, but the clarity and perception of her writing inspires to this day.