As part of her selection for Season Five, Her Royal Highness The Duchess of Cornwall has chosen the international hit by Italian author Elena Ferrante, My Brilliant Friend (2011). The first volume of the so-called Neapolitan Quartet, My Brilliant Friend tells the story of the formidable friendship between Elena and Lila, two young girls who grow up in a deprived neighbourhood of 1950s Naples, surrounded by violence and abuse, and their struggle for emancipation.

We are delighted to share an exclusive interview with Elena Ferrante, where the famously anonymous author discusses female friendship, education, rage, and the universality behind the story of My Brilliant Friend.

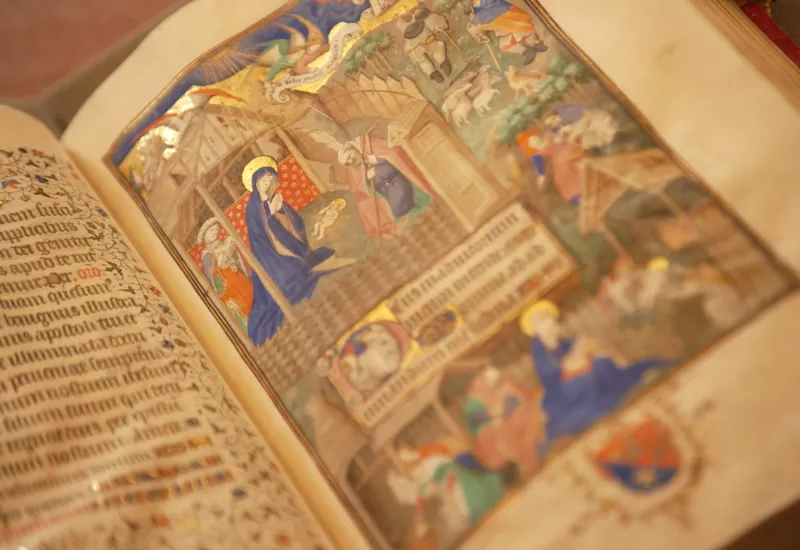

Pictures from the HBO adaptation of My Brilliant Friend.

The relationship between Elena and Lila is extraordinarily nuanced: bitter, competitive, vengeful, affectionate. What drove you to create their characters and what was it about female friendships that you set out to explore?

Among the things that have led me to reflect on friendship, I’ve always included the death of a friend who was important to my development. We were very close. After she died I dug deeply into our story and in the end I saw clearly that it had never been linear. So I started thinking about how often we use formulas that simplify the intensity and the contradictory nature of relationships. The expression “my best friend” is a lid stuck hastily on a pot that is permanently boiling. When I lifted that lid, many other stories of friendship emerged, from youth and adulthood, and I began to dig into those. The rest is making use of the literary tradition, imagination, language.

Does education emancipate us? Does it free us from violence? And what does it truly mean to be clever, or intelligent?

A good education, good schooling, helps us understand what world we’ve been thrown into at birth. But mainly it’s a tool for individual self-control. In an educated person, for example, aggression is reduced, is kept under control. So no, education doesn’t free us from anything. Rather, it enhances our good qualities and keeps our bad feelings in check. As for intelligence, it’s not necessarily synonymous with being well educated. One can be well educated and obtuse, or uneducated and extraordinarily perceptive. Intelligent people have eyes in the back of their head and are able to look beyond their own nose, apart from schooling. But, that said, it should be emphasized that intelligence without education is an abominable waste for the entire human race. How much female intelligence has, over the centuries, gone to waste? Preventing women from being educated has been and is an unforgivable crime.

Do you consider female rage a violent emotion, to be tamed, or does it sometimes serve a higher purpose?

Rage should be controlled and directed. An individual outburst of rage is often a helpful release. But the world won’t change unless rage becomes a political tool of liberation.

This is a story born out of a specific neighbourhood in Naples; but how much of the story do you think is universal?

You can’t plan universality or measure it with ruler and compass. Even though the writer always aspires to universality, all stories are essentially local and are nourished by very particular historical conditions. Troy is an ordinary, normal city before becoming the literary Troy we know. That is to say that the capacity of stories to speak to anyone and in any time is the fruit of a mysterious mixture of sensibility, ability, and luck, and no writer really knows how that fruit ripens and if it has fully matured. Every work is a forest, easy to navigate or complex. But the forest that all of us, writers and readers, aspire to is the one that, from the first lines, you feel is inhabited by gods and therefore sacred.